不同形式的锌补充剂

锌在小肠中被吸收。锌是聚合酶和蛋白酶的辅助因子,参与许多细胞功能(如伤口修复、 肠上皮细胞再生)。

尽管锌在人类生理上有许多重要的作用,但没有可靠的数据支持锌状况正常的人单独补锌(微量元素)。

锌与抗氧化剂结合使用,可能对减缓老年性黄斑变性的进展有一定的效果。

对于生活在世界发展中地区的儿童来说,补充锌可能是预防腹泻和尿毒症的有效措施,也是腹泻的辅助治疗手段。锌已被证明是治疗威尔逊病的一种有效方法。

目前还没有发现锌对上感(急性上呼吸道感染,又称感冒)、伤口愈合或HIV的治疗有公认的好处。持续补充锌至可耐受的摄入量上限通常是安全的。

由于胃肠道不良反应、铜缺乏、贫血和泌尿生殖系统并发症的风险增加,更高的剂量应限于短期使用。

锌是体内分布第二丰富的微量元素,仅次于铁。、

在美国 2002年全国健康调查中,2.5%的成年人报告说在上一年使用了锌补充剂。 62%的成人使用多维片,含7.5到15毫克的元素锌。

锌补充剂通常用于缓解一些情况,包括缺锌状态、腹泻、老年黄斑变性、上呼吸道感染、伤口愈合和人类感染。

【销售焦虑】

锌是人类新陈代谢所必需的微量元素,可以催化100多种酶硫酸锌颜色,促进蛋白质折叠,并帮助调节基因表达。

营养不良、酗酒、炎症性肠病和吸收不良综合征的患者,缺锌的风险增加。

缺锌的症状是非特异性的,包括生长迟缓、腹泻、脱发、舌炎、指甲萎缩、免疫力下降和男性的性腺功能低下。在发展中国家,补锌对预防上呼吸道感染和腹泻可能是有效的,并可作为营养不良儿童腹泻的辅助治疗。锌与抗氧化剂结合使用,对减缓中晚期老年性黄斑变性的进展可能有一定的效果。锌是治疗威尔逊病的一种有效方法。目前的数据不支持补锌对上呼吸道感染、伤口愈合或人类有效。

在推荐剂量下,锌的耐受性良好。长期大剂量使用锌的不良反应包括免疫力下降、水平下降、贫血、铜缺乏以及可能的泌尿生殖系统并发症。

https://www.aafp.org/afp/2009/0501/afp20090501p768.pdf

......

市面上有许多形式的锌化合物。

以下是常见的补锌剂的锌元素的百分比。

常见的口服锌制剂元素锌含量(mg)

醋酸锌,30%锌,25毫克 锌元素含量(mg)7.5

醋酸锌,30%锌,50毫克 锌元素含量(mg)15

葡萄糖酸锌,14.3%锌,50毫克 锌元素含量(mg)7

葡萄糖酸锌,14.3%的锌,100毫克 锌元素含量(mg)14

硫酸锌,23%的锌,110毫克 锌元素含量(mg)25

硫酸锌,23%的锌,220毫克 锌元素含量(mg)50

氧化锌,80%的锌,100毫克 锌元素含量(mg)80

注:膳食补充剂的标准成分标签提供了产品中锌的形式名称和以毫克为单位的元素锌的数量。吡啶甲酸锌 20%。

抗坏血酸锌 15%

氯化锌 48%

硫酸锌 22%

碳酸锌 52%

枸橼酸锌 31%

双甘氨酸锌 25%

所谓的“三合一锌”是由吡啶甲酸锌、枸橼酸锌和硫酸锌组成,提供26.5毫克的锌元素剂量。

没有多少实质性的证据表明一种形式的锌比另一种形式的锌更有效,因为人体对锌的吸收受很多因素的影响。

有的研究表明,在某些情况下吡啶甲酸锌的吸收效果更好,但这是一项只有 15个测试对象的研究硫酸锌颜色,需要进行更多的研究才能得出真正“结论性”的结论。

应该注意的是,有许多变量影响锌的生物利用率和吸收,包括以前的锌摄入量。在制定营养策略时可能需要考虑的其他变量包括:

禁忌证、不良反应和相互作用

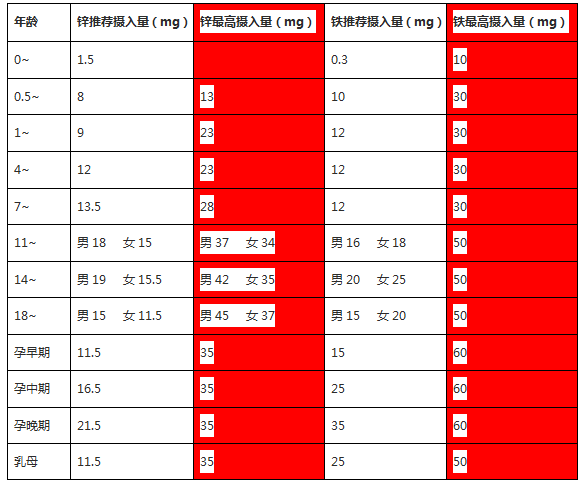

一般认为长期摄入锌补充剂达到可耐受的摄入量上限(成人每天40毫克元素锌)是安全的。

营养良好的孕妇和哺乳期妇女禁止使用超过可容忍摄入量上限的锌补充剂。

摄入过量锌的常见不良反应包括金属味、恶心、呕吐、腹部痉挛和腹泻。

对46,974名成年男性进行的健康专业人员随访研究发现,每天使用100毫克以上的元素锌的男性患晚期前列腺癌的相对风险增加。

铁剂和植酸盐(存在于谷物和豆类中)会抑制锌的吸收,应与锌剂至少间隔两小时服用。

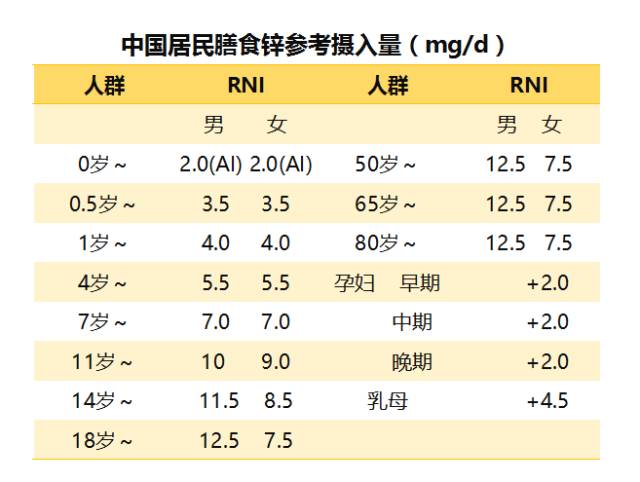

服用剂量

不同的锌保健品含有不同量的锌元素。

美政府对锌的摄入量的在 2016年膳食建议里可以找到。

锌的NRV()是每天10毫克,婴儿、儿童和青少年需要的量较少,孕妇和哺乳期的人则需要更多。

如果在这些方面遇到健康问题,而同时又缺锌,那么每天补充15-30毫克的元素锌可能会改善免疫力、眼睛、皮肤和其他方面的健康。

警告:

过量的锌摄入会引起负面的副作用,所以除非在医生的指导下,*好不要超过每天40毫克的耐受上限。

如果在服用锌补充剂后出现任何负面的副作用,请减少剂量,同时及时就医。

锌会干扰铜的吸收,并降低某些抗生素的效果。

锌是一种重要的矿物质,对健康有多方面的帮助。一般来说,锌不应在空腹时服用(因为它可能导致恶心),应与动物蛋白餐一起服用,远离谷物,并以保守的剂量服用以增加吸收。长期摄入锌会导致铜的缺乏,须平衡饮食。

参考

World Health Organization. The World Health Report, 2002: Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life. Geneva, Switzerland: :World Health Organization; 2002.

King JC. Zinc In: Shils ME, Shike M, eds. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 10th ed Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006: 271–285.

Institute of Medicine (U.S.). DRI: Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

Microminerals In: Groff JL, Gropper SA, eds. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism. 3rd ed Belmont, Calif: West/Wadsworth; 2000:401–470.

Timbo BB, Ross MP, McCarthy PV, Lin CT. Dietary supplements in a national survey: prevalence of use and reports of adverse events. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(12):1966–1974.

Cousins RJ. Systemic transport of zinc. In: Mills CF. Zinc in Human Biology. New York, NY: :Springer-Verlag; 198979–93.

Iwata M, Takebayashi T, Ohta H, Alcalde RE, Itano Y, Matsumura T. Zinc accumulation and metallothionein gene expression in the proliferating epidermis during wound healing in mouse skin. Histochem Cell Biol. 1999;112(4):283–290.

Cario E, Jung S, Harder D'Heureuse J, et al. Effects of exogenous zinc supplementation on intestinal epithelial repair in vitro. Eur J Clin Invest. 2000;30(5):419–428.

Mocchegiani E, Santarelli L, Muzzioli M, Fabris N. Reversibility of the thymic involution and of age-related peripheral immune dysfunctions by zinc supplementation in old mice. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1995;17(9):703–718.

Grahn BH, Paterson PG, Gottschall-Pass KT, Zhang Z. Zinc and the eye. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20(2 suppl):106–118.

Brown KH, Peerson JM, Rivera J, Allen LH. Effect of supplemental zinc on the growth and serum zinc concentrations of prepubertal children: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75(6):1062–1071.

Lukacik M, Thomas RL, Aranda JV. A meta-analysis of the effects of oral zinc in the treatment of acute and persistent diarrhea. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):326–336.

Aggarwal R, Sentz J, Miller MA. Role of zinc administration in prevention of childhood diarrhea and respiratory illnesses: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6):1120–1130.

Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8 [published correction appears in Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(9):1251]. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(10):1417–1436.

Evans JR. Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for slowing the progression of age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD000254.

Johnson AR, Munoz A, Gottlieb JL, Jarrard DF. High dose zinc increases hospital admissions due to genitourinary complications. J Urol. 2007;177(2):639–643.

Chong EW, Wong TY, Kreis AJ, Simpson JA, Guymer RH. Dietary anti-oxidants and primary prevention of age related macular degeneration: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;335(7623):755.

Tan JS, Wang JJ, Flood V, Rochtchina E, Smith W, Mitchell P. Dietary antioxidants and the long-term incidence of age-related macular degeneration: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(2):334–341.

Jackson JL, Lesho E, Peterson C. Zinc and the common cold: a meta-analysis revisited. J Nutr. 2000;130(5S suppl):1512S–1515S.

Prasad AS, Fitzgerald JT, Bao B, Beck FW, Chandrasekar PH. Duration of symptoms and plasma cytokine levels in patients with the common cold treated with zinc acetate. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(4):245–252.

Turner RB, Cetnarowski WE. Effect of treatment with zinc gluconate or zinc acetate on experimental and natural colds. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(5):1202–1208.

Prasad AS, Beck FW, Bao B, et al. Zinc supplementation decreases incidence of infections in the elderly: effect of zinc on generation of cytokines and oxidative stress. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(3):837–844.

Mossad SB. Effect of zincum gluconicum nasal gel on the duration and symptom severity of the common cold in otherwise healthy adults. QJM. 2003;96(1):35–43.

Kurugöl Z, Akilli M, Bayram N, Koturoglu G. The prophylactic and therapeutic effectiveness of zinc sulphate on common cold in children. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95(10):1175–1181.

Macknin ML, Piedmonte M, Calendine C, Janosky J, Wald E. Zinc gluconate lozenges for treating the common cold in children: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;279(24):1962–1967.

Rojas AI, Phillips TJ. Patients with chronic leg ulcers show diminished levels of vitamins A and E, carotenes, and zinc. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25(8):601–604.

Wananukul S, Limpongsanuruk W, Singalavanija S, Wisuthsarewong W. Comparison of dexpanthenol and zinc oxide ointment with ointment base in the treatment of irritant diaper dermatitis from diarrhea: a multicenter study. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89(10):1654–1658.

Wilkinson EA, Hawke CI. Does oral zinc aid the healing of chronic leg ulcers? A systematic literature review. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134(12):1556–1560.

Agren MS, Ostenfeld U, Kallehave F, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial evaluating topical zinc oxide for acute open wounds following pilonidal disease excision. Wound Repair Regen. 2006;14(5):526–535.

Bobat R, Coovadia H, Stephen C, et al. Safety and efficacy of zinc supplementation for children with HIV-1 infection in South Africa: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9500):1862–1867.

Leitzmann MF, Stampfer MJ, Wu K, Colditz GA, Willet WC, Giovannucci EL. Zinc supplement use and risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(13):1004–1007.

Walravens PA, Hambidge KM, Koepfer DM. Zinc supplementation in infants with a nutritional pattern of failure to thrive: a double-blind, controlled study. Pediatrics. 1989;83(4):532–538.

Nutritional disorders. In: Beers MH, ed. The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. 18th ed. Whitehouse Station, N.J.: Merck Research Laboratories; 2006: 55.-

营销型网站10大特点 兰州营销型网站的特征是什么发布时间:2024-11-25

-

新北区网站公司网站 南山汽车产业基地园区监控设备安装项目招标公告发布时间:2024-11-22

-

新北区网站宣传 常州市新北区台办五项举措做好涉台宣传工作发布时间:2024-10-16

-

营销型网站10大特点 网站开发:响应式网站如何兼顾营销型发布时间:2024-09-12

-

商城小程序开发费用 开发一个小程序商城要多少钱?发布时间:2024-08-13

-

金坛区网站招聘 网站优势/金坛人才网发布时间:2024-07-05

-

政府网站建设模板 政府网站建设工作的自查报告发布时间:2024-06-23

-

手机app开发源码 自建APP,不可错过的5个免费开发平台发布时间:2024-05-17

-

政府网站安全漏洞解读 挖政府网站漏洞被抓了,其实我只是想为家乡做点贡献?发布时间:2024-04-19

-

建网页有什么用 建站技术布局方式(网站推广建设人员)发布时间:2024-03-12

-

能做移动网站的公司 如何做移动端的官网?手机网站如何建设?发布时间:2024-02-20

-

营销型网站的优点 营销型外贸网站搭建?发布时间:2024-01-03